An article in a 1967 National Geographic magazine got me mulling over paddling around Japan. It described a combined USA – British college student paddle from the Inland Sea to Tokyo. Photographs of centuries old fishing ports and stunning coastal scenery spurred my interest. The team had bypassed the exposed east coast of Honshu due to heavy, prevailing surf, which also got my interest up.

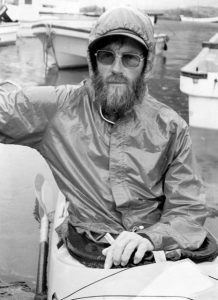

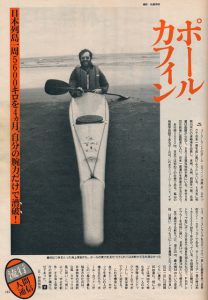

Grahame Sisson and I built Haya Kaze in Nelson, as I was keen to try out a microlight boat to see if higher daily averages distances were attainable. We used kevlar, carbon-fibre and vinyl-ester to build a 15 kilogram Nordkapp. The all-up weight included hatches, bulkheads and the aluminium, overstern rudder. A new seat was built, which when glassed into the cockpit, formed a third or middle bulkhead and a comfortable rigid, backrest. This minimized the amount of water which would enter the cockpit in the event of a capsize, and the middle compartment was easily accessible at sea with a VCP hatch just aft of the cockpit – very handy for cameras, the radio and my play-lunch.

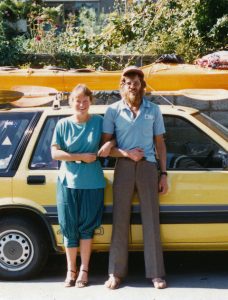

With my girlfriend Lesley Hadley as shore support, we achieved a memorable trip around Japan – I was then probably at my peak in terms of paddling fitness and stamina, knocking up 96 kilometre days with pre-dawn starts, and averaging 66 kms per day around Hokkaido.

‘Anata wa tabi wa do data?’ (How was your trip?)

‘Subarashi demmo muzukashi’ (Splendid but difficult).

Subarashi describes the beauty and contrasts of the coastal scenery, our contact with the Japanese fishermen, the magic of sunrises and sunsets and the faith and support from new friends we met around the coast.

An early response to a letter of inquiry was very succinct and to the point: ‘I do not think you should consider a paddle around Japan. Too many ships, too many people and too much pollution!’ But apart from some of the huge coastal towns and ports, the coastal scenery was superb, snow-capped volcanoes rising sheer out of the sea, tunnels, more caves than you could shake a stick at, massive archways I had to paddle through and a myriad of small fishing ports that could provide a movie set for James Clavell’s novel Shogun. Sections of the coast were so rugged and remote there was no sign of man’s presence.

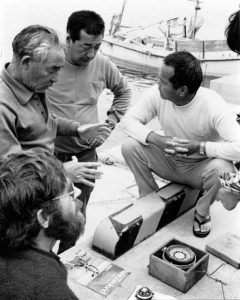

Japan must have the highest density of inshore fishermen in the world and summer was peak season for those harvesting seaweed and salmon. The port of Uketo on the Honshu coast had a fleet of over 200 boats which left through a narrow entrance between 3:00 a.m. and 3:30 a.m. The roar of the engines was like the noise of peak hour traffic in Auckland. I had no choice but to barge into the bow to stern line up of boats, but the experience of joining in that stream of boats speeding out to sea in the soft golden light of dawn was indeed splendid.

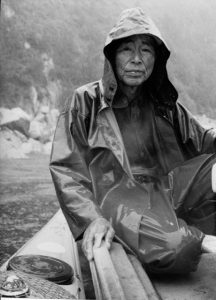

Many nights we slept by the open hearths of the ryoshi-no-banya (fishermen’s quarters), rising at 2:00 a.m. with the obasans (old ladies) who cooked breakfast over charcoal hearths, and departing before dawn with the fishermen. We were taken into the homes and hearts of the fishermen.

In marked contrast to previous ‘big trips’, no one person in Japan said I was crazy for doing the trip; instead they would call out ‘Gambate’, no exact English translation but a combination of good luck, try hard and show your spirit.

The Japan paddle was far more muzukashi (difficult) than I had anticipated. Taifu (typhoon) number 3 was in the offing when I commenced paddling on 26 May and number 13 gave me a dusting on the far north coast of Hokkaido. While plugging along the south coast of Honshu, three of the sods were in the offing, 12, 13 and 14. The taifu effects were felt four to five days after making landfall, with fierce winds, massive seas and thunderstorms. Doyonami is a specific Japanese word for swell generated by intense typhoons.

I completed the trip on 19 September with a 40 kilometre crossing of Tsugaru Kaikyo, the infamous narrow stretch of water between Hokkaido and Honshu. Total distance was 6,434 kilometres in 118 days for an all up average of 66 kilometres per day. All in all, it was a splendid but difficult trip.

Months later in New Zealand I received copies of various magazines which carried articles about the Japan trip. The January 1986 edition of Playboy included a seven-page pictorial of the trip with a male nude centre-fold picture. It was actually a pic Lesley snapped when I was showering under a roadside waterfall. The photo appeared by the central line of staples and although it was not exactly a centre-fold photograph, I like to kid myself that it’s close enough to being a nude centre-fold.

When Haya Kaze arrived back in New Zealand, aboard a huge container ship, I was trying to speed passage through the usual procedures of form filling and shuffling from department to department, by showing the Playboy to the chap from the Department of Agriculture and Fish. He said he would waive the normal $20 fee for the clearance if he could show the article to his rather attractive receptionist. I agreed. He asked her if she had ever met anyone who had posed nude for Playboy, and then showed her the photograph. And her comment, “You can’t see a lot!”

I reckon I got $20’s worth of embarrassment!